What a "Heart-Healthy" Diet Does to Your Cholesterol Levels

What happens when you follow the American Heart Association's dietary recommendations? You know, a diet high in whole grain, vegetables, fruit and berries, but low in animal protein and fat, especially that nasty artery-clogging saturated fat.

According to conventional wisdom, you will be healthier in general. In particular, your cholesterol levels are supposed to improve – though it's never quite clear what "improvement" here means. Is it lower total cholesterol? Or perhaps lower LDL and higher HDL? And what about triglycerides and oxidized LDL?

Fortunately, a few years ago the Journal of the American Heart Association published a study that looked at what happens to cholesterol levels while on the officially heart-healthy diet (link). In contrast to many other studies, the participants in this one were healthy and had normal cholesterol levels to begin with. The idea was to see whether adopting an optimal diet would make them even healthier.

Study design and composition of diets

The study included 37 healthy women and consisted of two phases. During the first phase, the women followed a low-fat, low-vegetable diet for five weeks. After that, there was a three week washout period, followed by the second experimental diet. This second diet was the "optimal" diet, which was also low-fat but this time included lots of vegetables, fruit and berries. To make sure that the dietary guidelines were followed, the meals were supervised.

Both diets included 8 portions of grain products, 3-4 portions of low-fat or fat-free dairy products, and 2 portions of lean meat, chicken or fish. In the first phase, the subjects were given 2 portions of fruit and vegetables per day. In the second phase, the amount of fruit and vegetables was increased to 4-5 and 5-6 portions, respectively.

Dietary fats were replaced vegetable oils and spreads which contained minimal amounts of trans fats. The amount of total fat and saturated fat decreased, whereas the amount of polyunsaturated fats increased. To replace the lost calories, the subjects ate more carbohydrates and protein. Fiber intake also increased; in the second phase, it was nearly twice as much as at baseline.

Thus, both diets were very close to official recommendations: they included only moderate amounts of fat and animal protein, the fat was mostly from vegetable oils high in polyunsaturated fatty acids, dairy products were low in fat or fat-free, and grain products high in fiber were included. In addition, the second phase was high in veggies, fruits and berries.

HDL, LDL and triglycerides

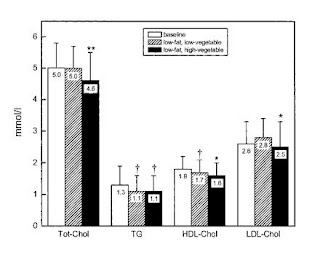

After the low-fat, low-vegetable phase, total cholesterol was unchanged. On the other hand, triglycerides and HDL decreased, while LDL levels increased. The increase in LDL was apparently not statistically significant, which is probably due to the small sample size.

When the amount of vegetables, fruit and berries was increased, total cholesterol decreased. Triglycerides remained the same, but both HDL and LDL decreased:

Thus, reducing the amount of fat in the diet and replacing animal fats with vegetable oils did not change total cholesterol but did change the cholesterol profile: HDL and triglycerides decreased, while LDL increased. From the "good cholesterol, bad cholesterol" standpoint, adopting a low-fat diet actually changed things for the worse.

Things were not much better when vegetables, fruit and berries were added to the low-fat diet. Total cholesterol was clearly reduced, which by some standards is admittedly a positive change. Importantly, however, this change was not achieved through a decrease in "harmful" LDL but in "healthy" HDL.

The amount of triglycerides did decrease compared to baseline, but the reason is unclear. Generally, replacing fats with carbohydrates seems to increase triglycerides. Also, triglycerides decreased after the first phase, when the diet was low in vegetables, and did not decrease further after the second phase, so dietary antioxidants don't seem to be the explanation either. One thing that comes to mind is alcohol intake, which is not reported in the study. Perhaps the subjects reduced their alcohol intake while on the experimental diets? That would show up as a lower triglyceride score, but we can't know for sure.

Oxidized LDL and lipoprotein (a)

Both oxidized LDL and lipoprotein (a) are independently associated with a higher risk of atherosclerosis – more so than total cholesterol or LDL. In fact, oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) is believed to cause clogging of arteries and inflammation. Lipoprotein (a), also called Lp(a), is a known risk factor in many cardiovascular diseases, although its function is not entirely understood.

The most interesting result of the study is that the number of oxidized LDL particles and Lp(a) increased significantly as a result of following the low-fat diets. Oxidized LDL increased by a whopping 27% in the first phase. Even after vegetables, fruits and berries were added to the diet, ox-LDL levels were still 19% higher than at baseline. Similarly, Lipoprotein (a) was 7% higher after the first phase and 9% higher after the second phase compared to baseline.

What this means is that two important risk factors of atherosclerosis worsened markedly after following the very dietary recommendations that are supposed to reduce risk of atherosclerosis. Although plasma antioxidant capacity correlated with the intake of fruit, vegetables and berries, the antioxidants in them were clearly not enough to protect from these harmful changes.

The changes in total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides were relatively small, which may be partly due to the short duration of the study. However, the 27% increase in ox-LDL demonstrates that diet can have a dramatic even in a short period of time.

Conclusion

The authors describe the results as "unexpected". According to them, a decreased intake of fat – especially saturated fat – should have led to a decrease in risk factors. They quote a number of studies where replacing saturated fatty acids with polyunsaturated fatty acids led to a "beneficial" decrease in total cholesterol. So why did the risk factors of atherosclerosis not see a similar "beneficial" change?

It is true that fats and oils high in polyunsaturated fatty acids generally tend to lower cholesterol (although the relationship between different fatty acids and cholesterol is more complicated than that). A completely different question is whether total cholesterol even matters, however. Even official recommendations acknowledge that the ratio of LDL to HDL is a better predictor of CVD than total cholesterol.

As was to be expected, the low-fat diets in this study did reduce total cholesterol. But if that decrease happens by reducing HDL and not changing or even increasing LDL, is the change really for the better? Most importantly, if the drop in total cholesterol comes with a marked increase in Lp(a) and oxidized LDL, can the results really be seen as beneficial?

Since the results of the study are incompatible with the cholesterol hypothesis and dietary recommendations, the authors came up with an alternative explanation. According to their hypothesis, high Lp(a) and ox-LDL may in fact be a sign of existing artherial damage being fixed and therefore a positive thing – but of course only in the case of low-fat diets. Right.

For anybody who has been keeping up with the gradual destruction of the cholesterol hypothesis, these results are not all that surprising. For example, we already know that polyunsaturated fatty acids oxidize much more easily than monounsaturated or saturated fats. It seems logical that LDL would be oxidized also.

What is somewhat surprising, however, is that the study was published in a journal that promotes the official dietary recommendations as heart-healthy.

For more information on cholesterol and diets, see these posts:

Which Oils and Fats Are Best for Cooking?

Carotenoids and Lipid Peroxidation: Can Vegetables & Fruit Reduce ALEs?

Sugar and AGEs: Fructose Is 10 Times Worse than Glucose

Anthocyanins from Berries Increase HDL and Lower LDL